Introducing the Global Pulse Indicators

Tracking AI’s Societal Impact

By Guest Contributor Brandon Jackson

No one knows what transformational change from AI will look like. It might be obvious: a sudden surge in economic productivity, a memorable moment when the future visibly tilts. Or quiet: a series of imperceptible shifts that are difficult to attribute to AI. Recent history is full of examples like globalization and social media that show how difficult it is to make sense of sweeping change while it is happening.

If we are to understand and steer the societal impacts of AI in real time, we need to extend our monitoring infrastructure to capture the interplay between intelligent systems and societies. That's why we created the Global Pulse: a set of longitudinal indicators, updated every two months, designed to make the social, economic, and cultural impacts of the AI era visible.

These set of indicators complements existing measurements to help us understand where we are now. It complements economic statistics focusing on macro trends and AI safety systems that focus on model behavior in isolation with more granular measurements of how these systems are being used in a wide range of societies worldwide.

It also aims to help societies respond in real time. Existing global polling infrastructure tends to flatten complex views into responses to generic questions. The Global Pulse elicits meaningful individual assessments that together can reveal collective intelligence. We track three key areas: how AI diffuses through communities, how much it is trusted, and what people think about its overall impact.

Tracking AI Diffusion

Making sense of AI diffusion requires capturing how technologies are being integrated into communities and workplaces worldwide through slow, uneven processes. Global Pulse provides a granular view of these regional differences, tracking how AI adoption varies across different countries and cultures.

The perceptibility of change can have a dramatic impact on how societies respond. Thus far AI's integration into daily life is often invisible. Consider social media platforms: users interact with them constantly, but few recognize that feeds are powered by machine learning. Even as diffusion accelerates people may rarely see "intelligent systems." They might be embedded deep within institutions or be used to produce low-cost software.

That's why we aim to complement visible statistics like unemployment rates with perceptual questions, asking how often respondents notice AI systems and whether they see automation displacing humans in their communities and whether they know people who have lost their job to automation.

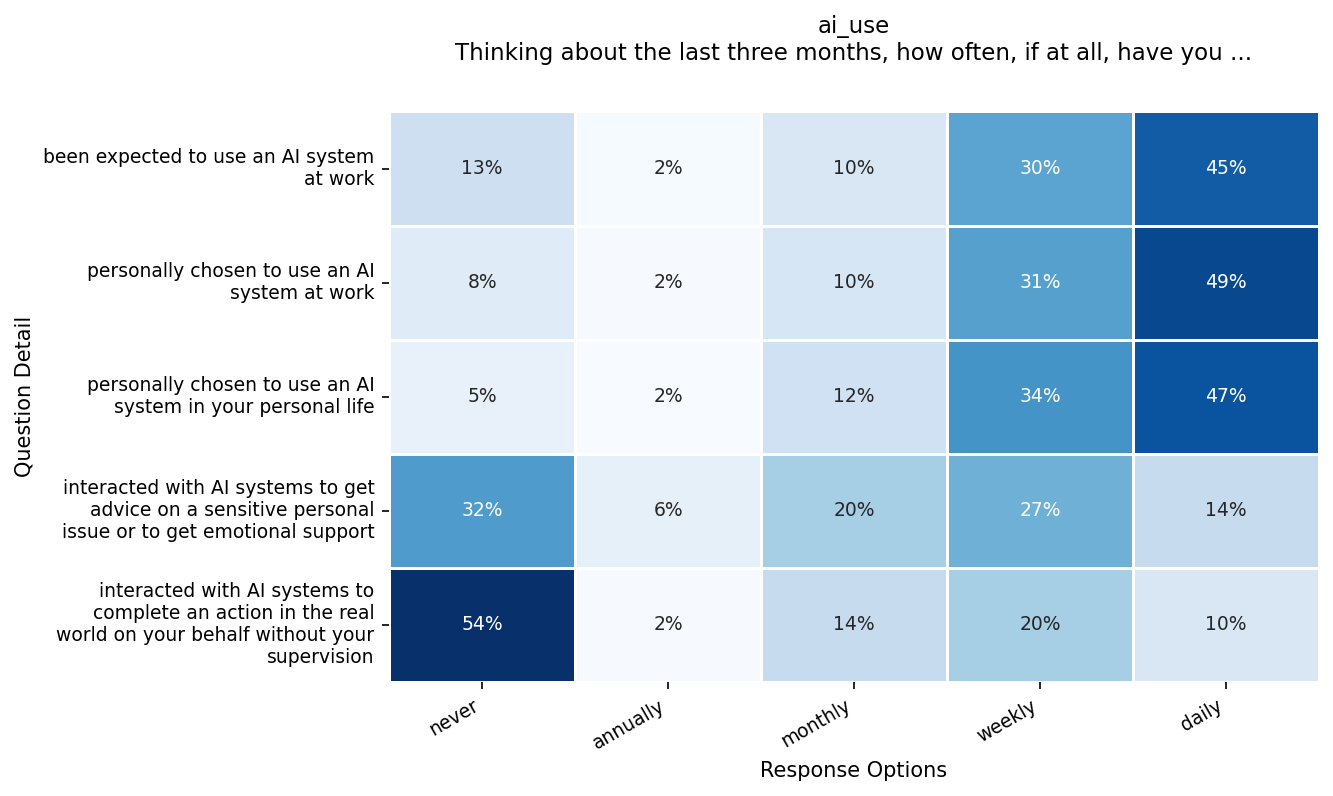

General usage stats also miss the stakes of AI deployment. We designed prevalence indicators to track higher-risk use cases:

At work: Are workers being expected to use AI, rather than choosing to?

For advice: Are people increasingly turning to AI for personal guidance?

Autonomous tasks: Are agents acting without human oversight?

By tracking these patterns across diverse communities every two months, we can capture how AI's impact varies by region and see how quickly new technologies reshape everyday experience.

Tracking Trust

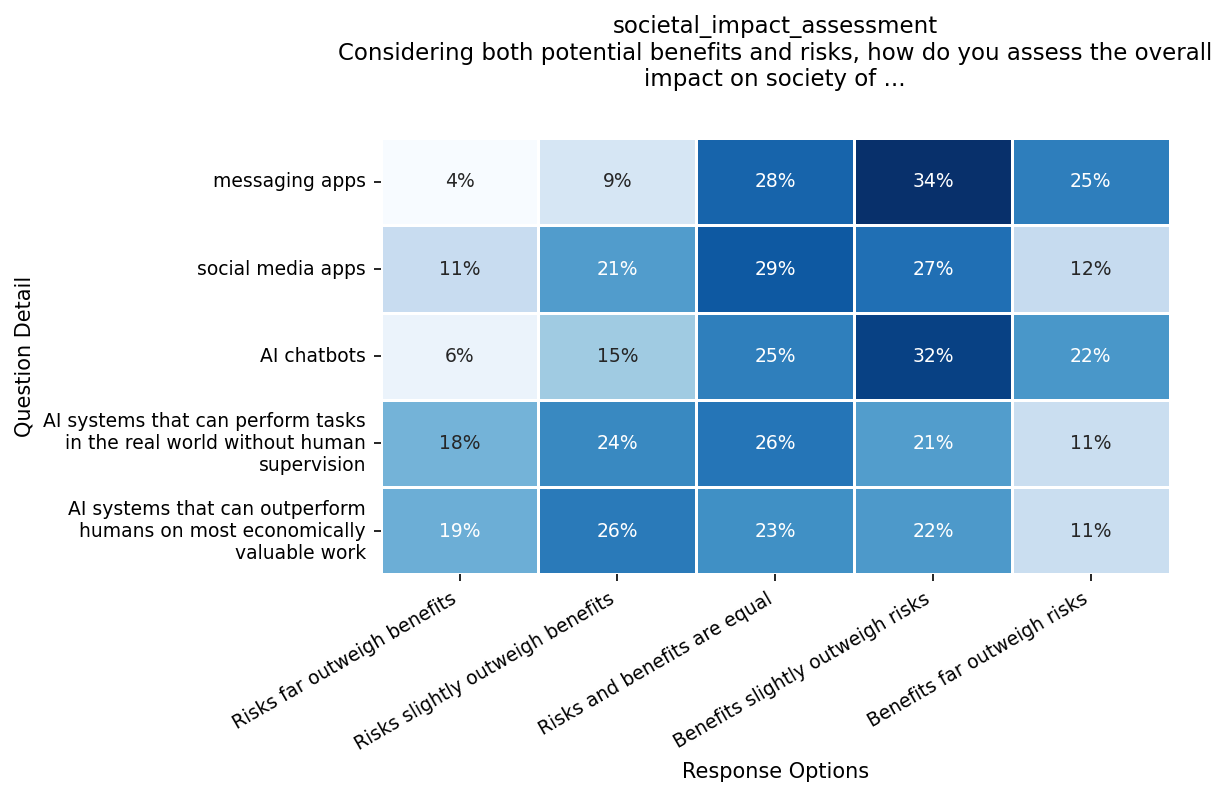

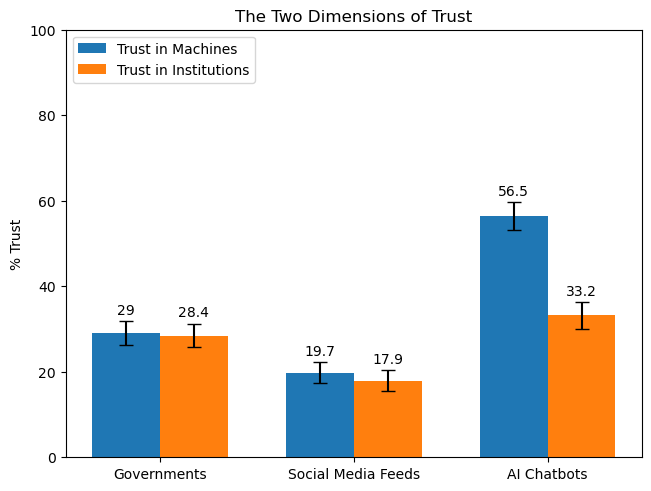

Trust is a vital ingredient for the widespread adoption of AI technologies. There is a growing effort to build AI systems that are more trustworthy. Meanwhile, there is also growing concern over the governance of the institutions that are building AI systems. To track changes in AI’s trust levels we expanded questions from traditional trust surveys to include AI and social media platforms alongside more familiar institutions like government and small businesses.

Trust also provides an index for understanding the changing relationships between the public, institutions, and AI. The reality is that trust in AI isn’t formed in isolation. It exists against the backdrop of record low levels of trust that existing institutions will do the right thing. To help directly compare trustworthiness, we asked respondents to rank how much they trusted different entities to act in their best interest, like:

Their family doctor, bound by a fiduciary duty of care

Their faith leader, bound by religious oaths

Their elected representatives, bound by public accountability

Their AI chatbots, not bound by a duty of care, oaths, or public accountability

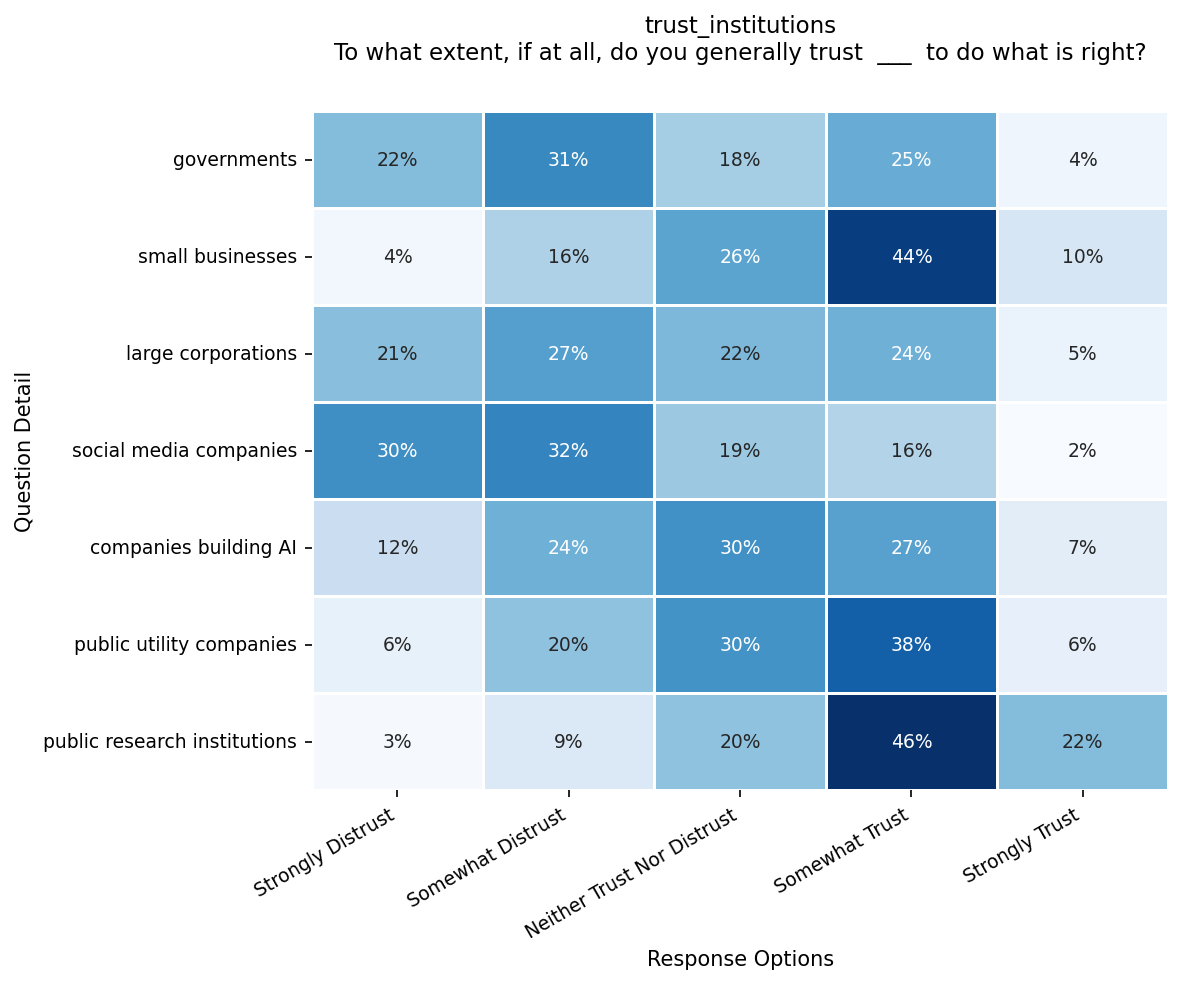

AI chatbots came second in trust levels, right after family doctors. They outranked elected representatives, civil servants and even faith leaders. When asked directly whether they trusted AI more than their elected representatives, only 29% said no.

A striking finding emerges: people trust chatbots more than the companies building them (p < 0.001). This breaks the normal pattern where trust in institutions matches trust in their services. This gap creates risks. AI systems seem caring through personalized responses, but unlike doctors or elected officials, they have no duty to users. This false sense of care can make it harder to question these systems or their creators. The stakes of AI’s trustworthiness are high for institutions. As it becomes more personalized and responsive, traditional institutions risk seeming even more unresponsive by comparison. They need to adapt or risk losing legitimacy to systems that feel more attentive but have no accountability.

Tracking Impacts Past, Present, and Future

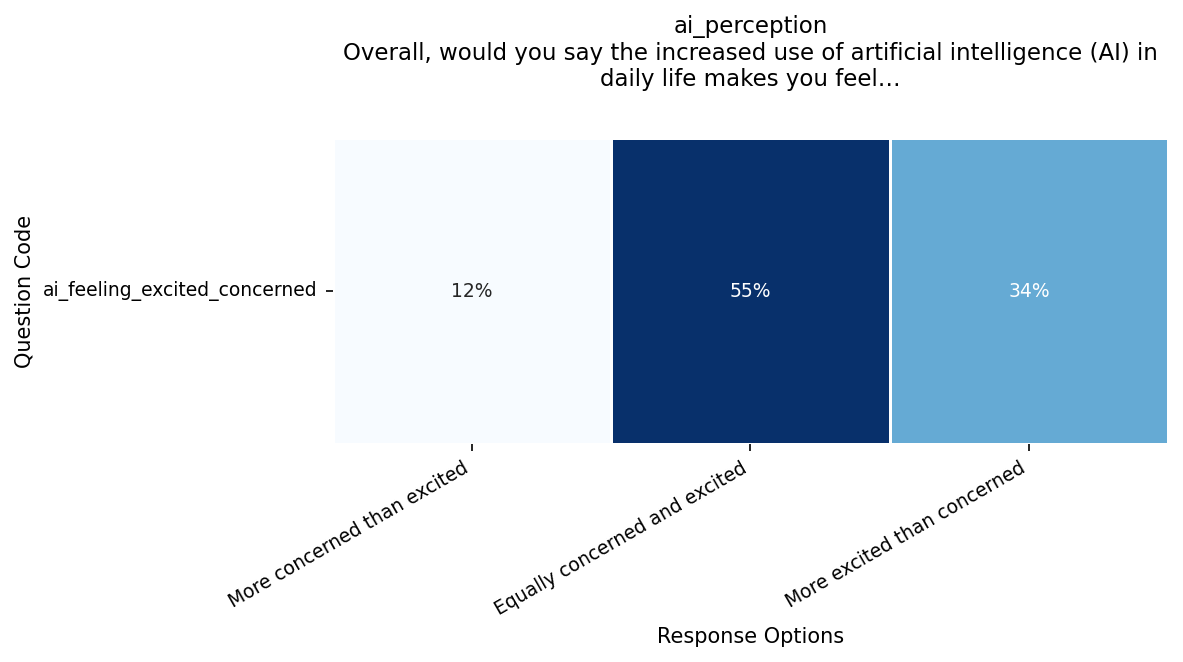

Steering AI’s development and adoption effectively requires signals about its overall net impact. Yet assessing this in real time is extraordinarily difficult. There is no single statistic that can tell us whether AI is making things better or worse. Instead, it requires a complex balancing of many factors. Rather than writing this off as an impossibility, the Global Pulse gives the public an opportunity to share how they weigh AI’s tradeoffs.

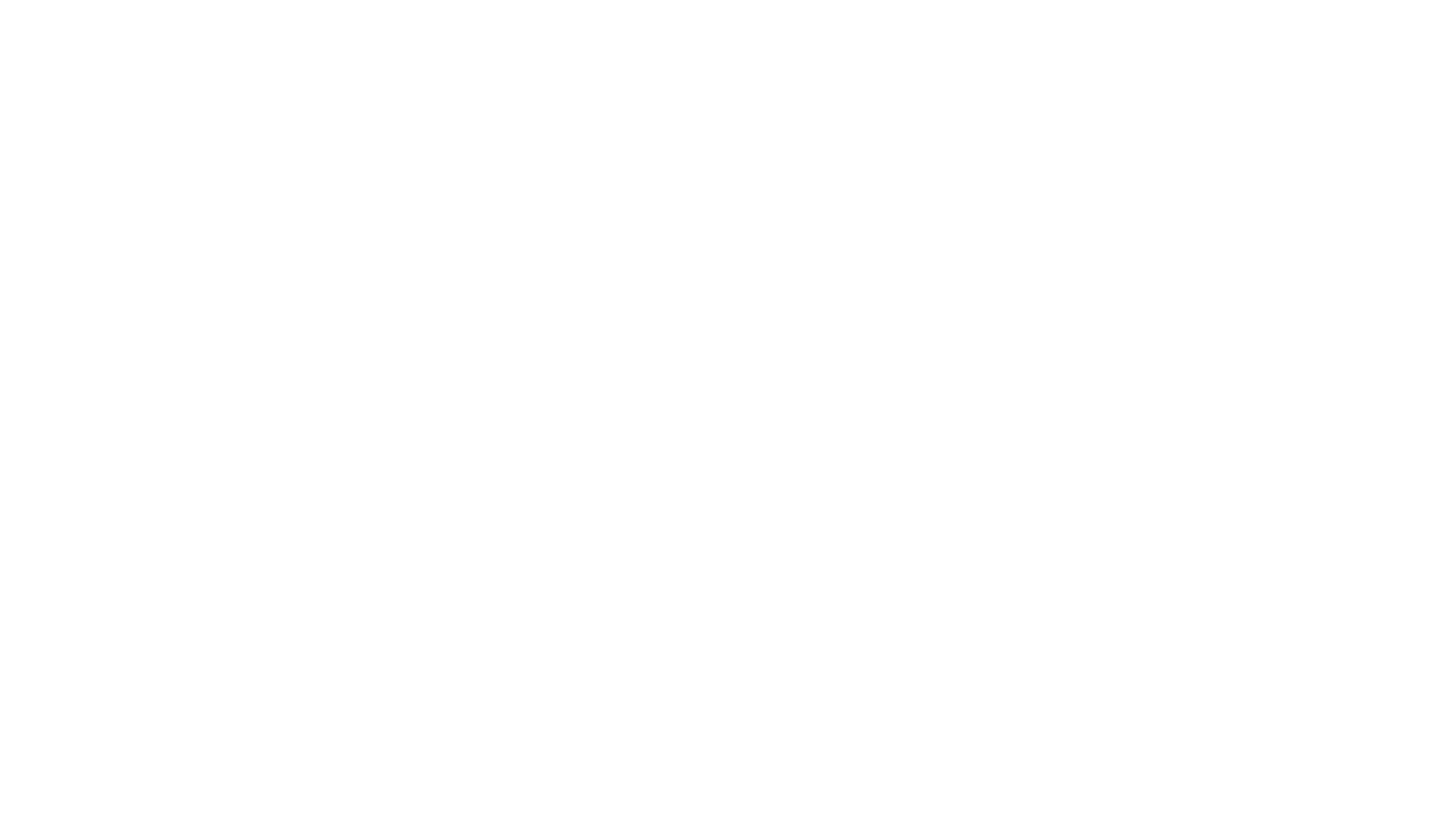

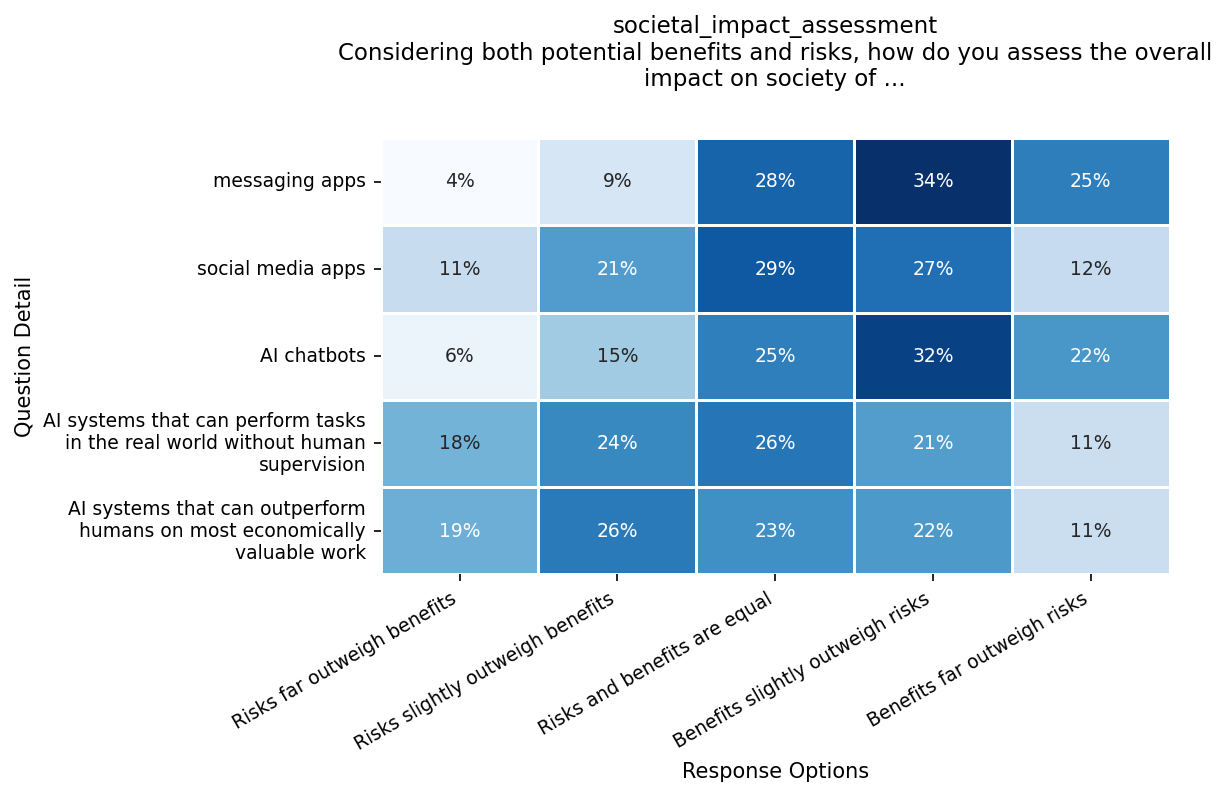

We asked whether people think different technologies are worth their risks, comparing older information technologies like messaging apps with current chatbot tools and frontier AI capabilities on the horizon like autonomous agents and AGI. The results show widespread skepticism. No technology received greater than 25% strong support, and net support for chatbots significantly outpaces that for autonomous agents or AGI.

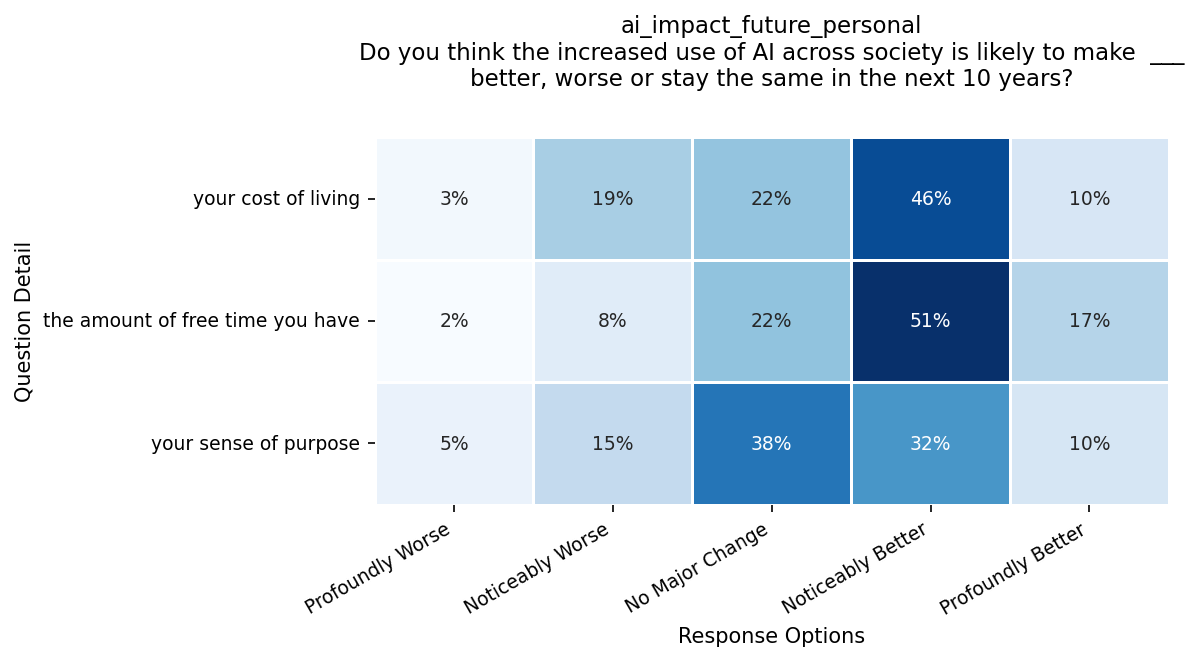

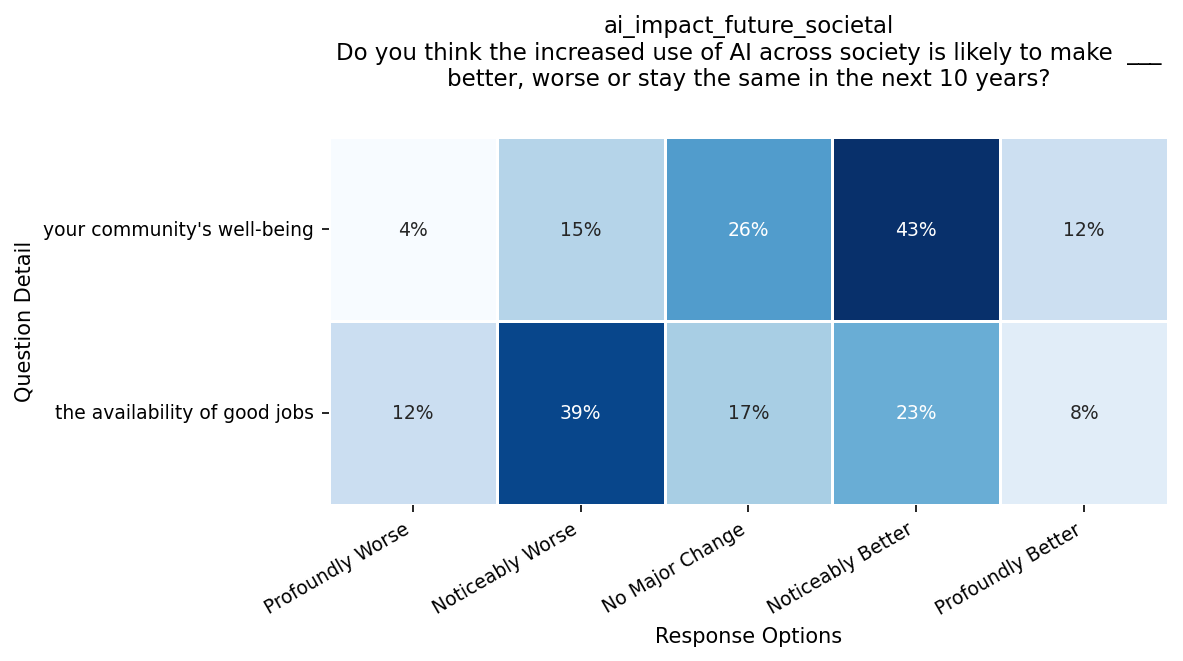

Looking ahead we wanted to understand public expectations about how daily life might change because of AI. We created a five-part scale inspired by standards of living frameworks, asking whether people expect AI to make aspects like cost of living or free time better or worse over the next decade. Even those who think it's likely they'll lose their job expect most things like cost of living and free time to get noticeably better. Yet at the same time very few (<15%) expect profound change in their daily life.

These questions give us an early warning system for social and political tensions. If people expect AI to improve their lives but then see costs rise or jobs disappear, that gap between expectation and reality could drive demands for new regulations or restrictions.

Conclusion

Trust, diffusion, and perceived impacts are fragmented and deeply contextual. People are already making sophisticated, and sometimes contradictory, trade-offs in their daily lives for AI. We’ve identified interesting, seemingly paradoxical, patterns from the data: citizens trust unaccountable chatbots more than their own elected leaders, and individuals bracing for job displacement still expect AI to improve their quality of life.

These data points are reflections of societies absorbing these transformative technologies. With clearer visibility into these dynamics, we can move from reactive responses to more intentional choices about the future we're building together.

Additional Figures

Brandon Jackson is an expert in product innovation at the Public AI Network, an international coalition of researchers working to make the case for public investment into AI. He has over 15 years of experience building public-interest technologies in mission-driven start-ups in both the US and UK tech ecosystems. He has a BA in computer science from Yale University and an MPhil in the history of science and technology from the University of Cambridge, where his research centred on the public adoption of new technologies such as radios.